How to slow down satellite rotation ? - The B-dot algorithm

The primary purpose of the Attitude Determination and Control System (or ADCS) is to control the attitude of the satellite (as its name would suggest). In the case of ECE³SAT, this will be done by interacting with the Earth’s magnetic field.

How so ? By using magnetorquers, which are just some kind of coils used to produce a torque, thus so adjusting the satellite’s rotation.

Most certainly, the nanosatellite will undergo some rotation at various stages of its flight: upon separation with the PPOD launcher (or any other launcher) or when deploying the antennas or the Electrodynamic Tether. In all these situations (and even more) a perturbation torque will be applied to the CubeSat, making it a freely spinning unusable orbiting junk. And for sure, we don’t like space junk… Thus, the very first step of any attempt to control the attitude in a stable way should be to reach a rather small rotation velocity (and to keep it throughout time). Only then can we try to point to a more specific direction.

This is why a detumbling algorithm is needed. And that’s where the BDOT algoritm comes up: it provides a simple way to reduce the angular speed.

But first, let’s recall how magnetorquers may be used to act on the satellite’s rotation.

How to use the actuators?

When the magnetorquers are supplied appropriately, they can generate a torque, obeying the law: [ \vec{T} = \vec{M} \times \vec{B} = \|\vec{M}\| \|\vec{B}\| \sin(\theta) \vec{u} ] where $\vec{M}$ is the magnetic moment of the dipole (the coil), $\vec{B}$ is the Earth’s magnetic field, $\theta$ is the angle between $\vec{M}$ and $\vec{B}$, and $\vec{u}$ is the unit vector resulting from the cross-poduct and is orthogonal to both $\vec{M}$ and $\vec{B}$).

Hence, the torque is maximal when the magnetic moment of the magnetorquer and the magnetic field are orthogonal (i.e. when $\theta = \frac{\pi}{2}$).

This means that the satellite, which is rigidly linked with the magnetorquers, will have the tendancy to align itself in a way that the angle between each of the coils’ magnetic moment and the Earth’s magnetic field is minimised.

Thus, to control the attitude of the satellite, one has to control each of the three magnetorquers’ moment which is ruled by: [ \vec{M} = i \cdot n \cdot \vec{S} ] where $i$ is the intensity of the current flowing through one magnetorquer (in A), $\vec{S}$ is the surface enclosed by a turn of the coil’s spiral (in m²) with a vector direction normal to this surface and $n$ is the number of spires of the coil. In our case, each element of this equation is fixed except the current intensity. Therefore, controlling the sign and magnitude of the intensity in each coil will determine the rotation direction implied by the resulting torque.

How does the B-dot work?

The principle of the B-dot algorithm relies on the usage of magnetorquers to generate a torque which is opposed to the “natural” rotation of the satellite (based on Newton’s 2nd law equivalent for rotational motions). This is made possible by applying an alternating positive/negative current to the coil to have an appropriate magnetic moment (see the equations in the previous section).

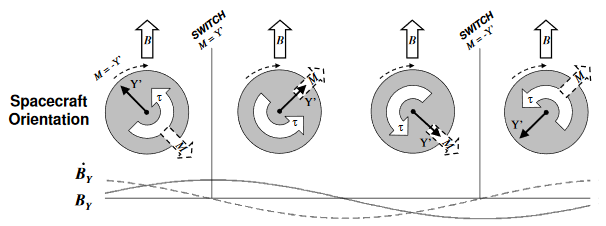

For instance, as seen on Figure 1:

- Given a satellite which magnetorquer is aligned along a Y axis fixed with the satellite’s rotation;

- When the satellite is rotating so that the Y axis is progressively pointing in the same direction as the Earth’s magnetic field, the temporal derivative of B, or rather its projection on that same Y axis, will be positive (i.e. $B_Y$ increases and $\dot{B} > 0$);

- A control signal with the opposite sign of the aforementioned derivative (thus a negative current) is sent through the coil so that its magnetic moment $\vec{M}$ points to the -Y direction;

- When Y passes B and moves further away (that is to say when $\dot{B}$ is negative), the dipole orientation of the coil is then reversed so that the sign of the resulting torque is preserved.

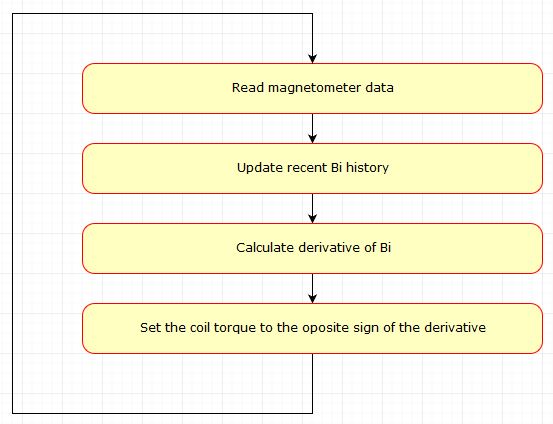

To sum up the way the B-dot algorithm works, here is a simple flow chart:

The control law creates a magnetic dipole in the opposite direction to the change in the magnetic field, estimated with magnetometers data: [ M_i = -k_i \dot{B}_i ] (with $i$ being one of the three axes and $\dot{B}_i$ the temporal derivative of the $\vec{B}$ field with respect to this axis)

As we have seen the B-dot algorithm is a rather simple stabilization algorithm which only requires knowing the evolution of the magnetic field as measured by our CubeSat’s sensors.

A few things to note, though:

- We haven’t covered the way we compute the derivative of the magnetic field from the values we obtain from the sensors, but this should be fairly simple if we follow the mathematical definition of a derivative;

- We haven’t covered the method used to tune the coefficient

- You should as much as possible run unit tests and functional tests of your control algorithms both in a high-level simulation environment and on the target hardware. This helps designining, fine-tuning and understanding the algorithms behaviour and also generally eliminates most of the elementary mistakes made during implementation;

- Power consumption on-board the satellite will often be critical ! It is important to have this in mind when implementing algorithms. The B-dot is rather economic in terms of computational power but the activation of magnetorquers doesn’t have to continuously be ON 100% of the time. And besides energy considerations, it is also essential that the values read from the magnetometers are not influenced by the magnetic field that we generate from the magentorquers. But these practical considerations may be the subject of a future article. 😉

Lastly, if you are interested in attitude determination or control algorithms, feel free to check the Wiki part on the ADCS from times to times as we will try to progressively add more descriptive content there.